Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

Background Information on Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

Principles to Support Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

Spotlight on Students: Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

When young people arrive to U.S. schools from other countries, they may feel overwhelmed by all the new things they encounter. As teachers, we can also find it challenging to meet the diverse needs of newly-arrived students, due to their highly variable experiences, backgrounds, and levels of comfort in school settings. This resource is meant to help you understand, educate, and advocate for this student population.

The ideas and examples we will share in this resource draw on the expertise and years of experience of the CUNY-NYSIEB support team, whose members have guided dozens of schools across New York State to develop best practices for Emergent Bilingual students, including Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals. We draw on our core principles in all the work we do, which view bilingualism as a resource in education and support a multilingual ecology for the whole school.

I. Background Information on Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

How do we get to know newcomer emergent bilinguals?

First of all, which students are identified as Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals? Essentially, if a student is born in another country and has recently arrived to the United States, he/she would be identified as a “Newcomer” upon enrolling in school. In this document, we will be focusing on Newcomers who are also identified as Emergent Bilinguals, meaning that they speak a language other than English (LOTE) as their home language and are learning English in school. An incredibly diverse array of students falls under the Newcomer Emergent Bilingual designation. A Newcomer Emergent Bilingual could range from a very young child just entering the school system whose home and new language practices are still developing, to a high school student who has well-developed academic skills in his/her home language. Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals also include students with other designations, such as SIFE (Students with Interrupted Formal Education), Refugee (students fleeing their country of origin because of persecution, war, or other disruption), or Unaccompanied Minor (children who arrive from other countries without their parents).

Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students vary in terms of…

- Nation of origin.

- Age at which they entered the U.S. school system.

- Language(s) they speak at home.

- Comfort with academic environments

- Access to schooling in their home country.

- Comfort with home language and English school-based literacies.

- Whether they studied English in their home countries.

- Socio-economic factors.

- Racial, religious, and ethnic identity.

- Extent of ties to family, friends, language, and culture abroad.

For more on identifying and supporting newcomer Emergent Bilinguals, check out this comprehensive resource from the US Department of Education:

What can schools do for Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals?

Just as with all Emergent Bilinguals, schools must provide newcomer Emergent Bilinguals with English development services. Because the needs of newcomer Emergent Bilinguals typically extend far beyond language support, schools may also provide special classes or other services developed for this population. Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals such as refugees or unaccompanied minors may have experienced trauma, while others, like SIFE students, may have an incomplete or insufficient school experience (Zacarian & Haynes, 2012). Newcomer Emergent Bilingual classes help students with unique needs adjust to life in a new country, where they are learning a new language and adapting to a new culture.

The following resources can help you get started if you are interested in developing a special class for Newcomers at your school. Both provide frameworks for designing programs that target the development of oral English skills, and help students catch up in core academic content areas and adapt socio-emotionally to life in the United States:

II. Using CUNY-NYSIEB Principles to Support Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

In our experience working with schools, a few strategies have stood out as particularly promising for Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals. We highlight classroom examples from CUNY-NYSIEB cohort schools where these strategies have been successfully implemented. We present them here divided into “school based” and “classroom based” practices, to differentiate between what we have seen successfully implemented on a schoolwide level and what individual teachers have accomplished with these students.

A. Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals on a Schoolwide Level

1. Get ready to support your Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals and their families from day one

Many of our cohort schools shared with us that when Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals arrived to their schools, they felt unprepared to support them. CUNY-NYSIEB has helped a number of schools establish key protocols for when these students arrive in order to ensure a smoother transition.

- Many of our cohort schools shared with us that when Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals arrived to their schools, they felt unprepared to support them. CUNY-NYSIEB has helped a number of schools establish key protocols for when these students arrive in order to ensure a smoother transition.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals from Day One

1. Identify and get to know your Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals: Research supports that an initial interview with family members and students enables schools to understand more about Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals’ educational histories, language experiences, and family life – and thus to better understand their strengths and needs (Brooks, 2017). One of our cohort schools created this sample intake interview for Newcomers. Please note that this interview should be conducted in the students’ home language when possible, and you should try to ask questions that encourage open dialogue. 2. Create a bank of “welcome to school” resources: Schools found it helpful to have a resource bank of materials or welcome kit they could use with Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals to help orient them to the school. We helped one of our cohort schools create a folder for parents containing information in the family’s home language on school policies, along with pamphlets from helpful community organizations. Another cohort school had success creating a welcome packet for Newcomer students that teaches basic school vocabulary and has some low-stakes activities for them to complete during the first weeks as they adjust to a new school. 3. Share a welcome video: Many school districts have “welcome videos” for newly arrived Emergent Bilingual students and their families; you can see a New York State parents orientation video example here. While these videos can be useful, it can be even more meaningful to create a “homegrown” video, as one of our cohort schools did. Working with their most valuable resources – their students – two teachers at this school created “welcome videos” for Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals in the students’ multiple home languages to orient more recently arrived students to classroom and school procedures (see classroom-based practices for more information on these videos).

2. Focus on community building across the school

Many schools we worked with had self-contained classes for their Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students, and felt these programs helped ease these students’ transition to a new school, culture, and language. While this was true, some of our cohort schools also realized that students were not integrating well into the broader school culture once they exited the special classes. Easing newly-arrived students into mainstream classes is important, given research showing that when Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals are isolated from their peers it can be detrimental to their language and social development (Carhill-Poza, 2017). One school worked strategically to provide opportunities for Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals to feel involved, develop strong relationships with peers and adults in their school community, and develop new language and social skills in authentic contexts through their Advisory program. This program had the dual benefit of also supporting students who were not recent arrivals.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Community Building with Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals At a grade 6–12 grade public school in a small city in New York State that receives large numbers of Newcomer students every year, strong relationships among students and staff are the basis of school culture. Prior to working with CUNY-NYSIEB, this school had created an Advisory program, which was devoted to building relationships and developing students’ socio-emotional well-being through short sessions 4-5 times per week. Just like all Advisory programs, their program incorporated circle time, a talking piece, and reflection time. With our support, school leaders transformed the program to incorporate supports for Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students, in order to ease their integration into the broader school culture. Supports added for Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals to the Advisory program:

- Newcomers and mainstream students are mixed together during Advisory.

- Clear routines posted in multiple LOTEs to provide Newcomers with support on following Advisory protocols and facilitate comprehension.

- Circle questions paired with language stems to build students’ socio-emotional vocabulary. A sample is: “What makes a good friend?” / “A good friend is…”

- Strategic pairings between “oldtimers” and “newcomers” and questions related to Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals’ experiences allows Newcomers to both learn from proficient language models as well as lead as “experts” on certain topics.

- Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students are allowed to participate in the circle in whatever language, and at whatever pace, they feel most comfortable, with peers or adult facilitators providing translation if needed.

After they had included Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals in the Advisory program for some months, teachers at this cohort school noticed Newcomers particularly benefit from circles, because they started to see themselves as valued and equal members of the classroom and school community. They began to share in English more, and establish friendships with kids in mainstream classes, which proved helpful for their development of their new language.

3. Welcoming Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students and their families by making their languages visible

One of the key principles of the CUNY-NYSIEB project is building a multilingual school ecology– that is, making sure the languages of Emergent Bilingual students are visible and utilized throughout the school building. This is especially critical for Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students. Many Newcomers are encountering English for the first time, as well as getting accustomed to a new school building. Multilingual signage around the school is helpful for basic navigation. One example of this is a cohort school where teachers and students labeled school locations multilingually (i.e. bathroom, library); another school placed a sign with commonly used phrases in the school’s main home languages to help parents communicate with school secretaries. Multilingual signage can also serve a deeper purpose than just communication: It helps students feel they belong when they see their languages visible in their schools.

| CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Making Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals’ Languages Visible |

| One of our cohort schools is a large, urban, K–8 school where a majority of students and/or families originally come from China. The school receives many Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals every year. At this school, a lower elementary ENL teacher and her students created a hallway bulletin board designed to teach passerbys words in Mandarin.

|

One final note: It’s okay to feel nervous about hearing languages other than English in your school and classroom! A lot of teachers at our cohort schools felt the same way at first – until they saw the benefits of being open to students using all their language resources in class. If you’re still unsure what this might look like, it could help to watch this short webseries on teaching bilinguals when you’re not one. You may also want to learn more about your students’ home languages to help you understand the way students language at home and at school.

B. Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals at the Classroom Level:

1. Pair Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals with a “buddy” (Language Partners)

Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students benefit from a “buddy” who can serve as a translator and help orient them to the school environment and make sense of class activities. Haynes (2007) describes an ideal buddy or language partner as another student in their class who speaks their language and may have previously been in their situation. One way our cohort schools have found this a useful strategy is by pairing English proficient students with peers newer to English who speak the same home language, and building in time for these students to discuss topics, texts, and tasks in the home language during small group work time. This strategy, also known as using “language partners” or “multilingual collaborative work,” is described in detail in the Collaborative Work section of our Translanguaging Guide.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Pairing Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals with a Buddy Our cohort schools frequently receiving new arrivals would describe their difficulty in supporting these students in their home language because they didn’t have the staff fluent in the numerous home languages, and their libraries lacked a diversity of home language texts. One CUNY-NYSIEB cohort school sought to mitigate this issue by tapping into one of its richest resources: its students. At this large, public high school in an inner-city neighborhood with high levels of new immigration every year, over 30 different languages were spoken by students and many Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals were enrolled at every grade level. Working in collaboration, CUNY-NYSIEB staff, the ENL Head Teacher, and administration developed a “peer tutoring program” that hired academically successful students bilingual in target home languages and English to become tutors for their peers. Provided with basic training, these teenage tutors were paid during their study hall periods to work with small groups of Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals in different subject area classes. The project was a great success for both the Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals – who had the invaluable support of home language explanations of challenging material – and the tutors – who gained confidence and job experience.

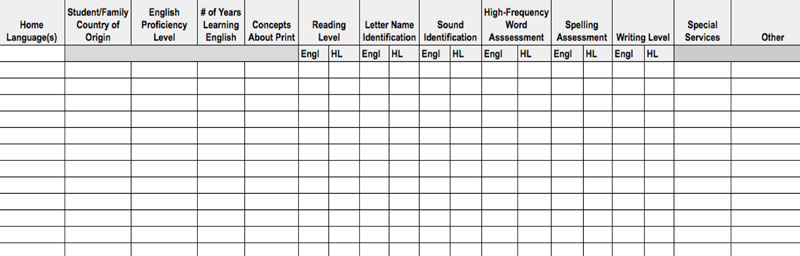

2. Develop holistic bilingual profiles of Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals in your class

One of our first steps when working with schools is to meet with administration and teachers to learn about how they hope to partner with us in supporting their Emergent Bilingual students. We are often surprised to learn that our schools and teachers are unaware of which home languages are spoken by their students. Performing a language survey can identify this information. But why is it important? Particularly when it comes to Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals, knowing what home languages students speak helps teachers identify resources to support them (i.e. texts, language partners), understand learning challenges in English (i.e. language transfer, concepts of print), communicate with family members, build a school ecology of multilingualism, and more. In her helpful guidebook to literacy and content instruction for Emergent Bilinguals, former CUNY-NYSIEB team member Christina Celic suggests building a holistic bilingual profile of students to get a better picture of the as learners. Such a profile includes information such as home language, country of origin, education and literacy in languages other than English, and whether a student is exposed to English at home.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Holistic Bilingual Profiles When we first started working with one cohort school, they knew about student home languages as percentages: The district informed them that every year, a certain percentage of the students identified as Emergent Bilinguals spoke Spanish, a certain percentage spoke Arabic, etc. After starting to work with us, administration urged teachers to conduct a language survey in all classes, in order to learn more about individual student language practices and begin building a school ecology of multilingualism. Surprisingly, they uncovered that a Newcomer Emergent Bilingual from Mexico in their Spanish-English bilingual kindergarten class was struggling in school because he was actually learning two languages at once: they found out his home language was Mixtec, an indigenous language, not Spanish! The school was able to switch his placement to ENL and begin working with family members on ways to support him through Mixtec. While not all schools will have such dramatic realizations when they identify students’ home languages, compiling this information is a critical way to understand your Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students as whole individuals, better enabling you to identify ways to support them. Note: Click on the above spreadsheet to go to a resource you can download and use in your own classroom.

3. Locate language resources within your school and community

When you learn that a Newcomer Emergent Bilingual in your classroom speaks a language you do not speak, or perhaps have never heard of, it can be challenging to know how you as a teacher can support this student in his or her home language. Many teachers we worked with voiced this concern. However, remember that as teachers, our main job is to plan, direct, and identify resources – and often the resources we need to support Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals lie not in our own skill set but rather can be tapped from within the community. Bilingual staff, aides, or advocates from local community groups can provide interpretation services for Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students (and their parents). Colleagues who see the student in other contexts (such as a “specials” teacher or ENL teacher) might have insights into a Newcomer Emergent Bilingual student’s abilities. Many cohort schools used the students themselves as language resources to teach each other; one of the most successful examples is described in continuation.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Students as Language Resources At an elementary school in a small city in upstate New York, administrators and teachers work hard to ensure that all Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students – and particularly the large refugee population – feel safe and welcome in their new school. Because these students come from distinct, and often very difficult, circumstances, the school knew it had to find resources from within the community that would help their students to adapt and feel comfortable. Through their work with CUNY-NYSIEB, two teachers and their students created short videos to welcome Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students and their families to the school community in a variety of languages. The teachers began by looking at their curriculum, and found an opportunity to link translanguaging strategies and the welcome video project with what students were already learning. Because the ELA curriculum required students in third grade to write informative expository essays, the two teachers decided to center the essay assignment on the question, “what should a new student know about our school?” Because all of the students had experience immigrating to a new school, and many of them were refugees themselves, the teachers asked them to draw on their own emotions and experiences to give advice to other Newcomers.

Students came up with a list of important things – from knowing where the bathrooms are to understandings how to talk to teachers – and then chose one topic to focus on. They wrote their essays in English independently, but in home language groups so they had support in their home languages from their peers during the drafting process. Using the information from students’ essays, the teachers used iPads to record students reading their essays in English and giving tours around the school in their home languages, pointing out the important things new students should know.The teachers edited the students’ essays and videos into more formal Welcome messages that new students and their families would view when they first arrived to the school. The teachers created videos in the top ten languages of the school and provided copies to homeroom teachers to show to Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals. As one teacher put it, “children learn best from other children, so this was a great student-led initiative” that drew on students’ linguistic expertise to help newly arrived students adjust to the school.

4. Plan for multilingual inputs and outputs

While they are acquiring English, you should encourage Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals to use their home languages to think, read, and write deeply and critically, and in authentic contexts (Fu, 2009). An example would be writing in the home language about an English-language text, or reading a home language text to get the background information necessary to complete a Science project in English. Whenever possible, you should assess students holistically, enabling them to show what they know in both English and their home languages (Mahoney, 2007). You should also plan to use multilingual and multicultural texts when possible (Celic & Seltzer, 2012).

5. Leverage home language practices and bilingualism as a resource

Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students bring with them the ability to use language in creative, flexible ways to communicate and express themselves. Draw on those abilities by encouraging students to speak, read, or write in their home languages, or express themselves across modalities other than just in speech or writing, so that they can participate and gain confidence in the classroom (Celic & Seltzer, 2012; García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017).

6. Use technology resources strategically

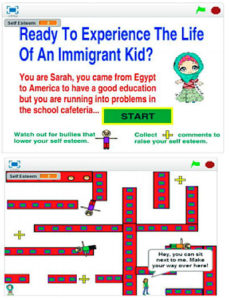

It cannot be argued that most people these days rely on technology to interact with the world, whether through a smartphone, tablet, or computer. Many Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students rely on technology to communicate with family and friends in their home country, or use web-based apps or translation software to help them learn and practice their developing English. Digital tools and technologies offer a wealth of resources to be used with and by Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students, for instance to read or view content area information in the home language, translate home language and English texts, and more (España, 2016; Celic & Seltzer, 2012). Students in CUNY-NYSIEB cohort schools have successfully used technologies in multiple ways, even to compose multimedia texts that integrate images, recordings, video, and other media.

| CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Supporting Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals with Technology |

Note: This example comes from the CUNY-NYSIEB Translanguaging Guide for Writing One cohort school had success working in conjunction with CUNY-NYSIEB and the non-profit Global Kids on a project where students used Scratch to write a videogame based on their own experiences as newcomers to the U.S. The game they designed puts players in the shoes of a newly-arrived student from Egypt, Sarah, who is teased about wearing a headscarf. Not only did Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students practice writing and gain programming skills, they were able to discuss real world issues that affected them by playing the game with peers and teachers. |

Spotlight on Students: Newcomer Emergent Bilinguals

Because, after all, our main goal as teachers is to support our students, we provide here a few profiles of Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students from our Cohort schools who received different types of support to meet their diverse needs. Reading through these profiles can help you see what resources schools used, how they supported students, and the results of these supports.

Isabela, 6, Kindergarten Student from Guatemala

Isabela is a 6-year-old born in Guatemala. She arrived to the U.S. the summer before starting Kindergarten, and enrolled in school for the first time ever, in a small city in upstate New York.

Isabela is a 6-year-old born in Guatemala. She arrived to the U.S. the summer before starting Kindergarten, and enrolled in school for the first time ever, in a small city in upstate New York.

This child’s journey to the U.S. was very difficult. Mounting gang violence and instability had made Isabela’s family feel unsafe so she and her father left Guatemala to join relatives who had moved there decades earlier. They were apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border, and after months in a detention center Isabela was released to relatives in the U.S. but her father was deported back to Guatemala.

Teachers and administration worked closely with family members on a specialized program for Isabela, to support her both academically and emotionally. For instance, in addition to completing an academic screening in English and Spanish, they also scheduled weekly appointments with the district’s bilingual social worker. Isabela was placed in a kindergarten class taught by a teacher who had also taught her cousins, which allowed the school to continue building their partnership with Isabela’s family.

Since she had no formal schooling in Guatemala, Isabela knew only two letters and two numbers in Spanish and had virtually no exposure to English. The school team arranged daily, one-on-one ENL instruction for her that helped her build both language and school skills. She was strategically placed with a bilingual ENL teacher, who helped her use her well-developed oral Spanish skills as she was acquiring English. Isabela’s kindergarten teacher also encouraged her to use Spanish in class while learning concepts and vocabulary in English.

Nine months after arriving, Gabriela is thriving. Both her ENL teacher and classroom teacher now describe her as very motivated to learn and to read. By the end of the school year, she knows the English alphabet, can read many sight words, and is comfortable talking with teachers and other children in English and Spanish.

Kasun, 10, 4th Grade Student from Sri Lanka

Kasun is a 10-year-old born in Sri Lanka who arrived in the U.S. at the beginning of 2nd grade. His parents speak both English and Sinhalese to him and his older sister. Though Kasun usually answers back in English, he understands Sinhalese.

Kasun is a 10-year-old born in Sri Lanka who arrived in the U.S. at the beginning of 2nd grade. His parents speak both English and Sinhalese to him and his older sister. Though Kasun usually answers back in English, he understands Sinhalese.

Kasun comes to school with prior knowledge on many different topics, thanks to his home life experiences, and his formal kindergarten and 1st grade education at a private school in an urban area in Sri Lanka. He expresses curiosity about the topics he studies, such as manatees and rocket ships, but also loves telling stories about Sri Lanka. He is enthusiastic and eager, and always willing to share. His ENL teacher mentioned that Kasun is never short on ideas; that anything you ask him about, he will have a story.

Kasun has made measurable growth on the state assessment of English language proficiency since arriving, and his ENL teacher expects he may score at or near proficient on the state English Language Arts exam this year. He benefits from an encouraging 4th grade teacher who has a keen understanding of his intelligence and who values his work. Additionally, his ENL teacher uses visuals, explicitly models problem-solving and writing activities, and helps him break tasks up into steps. He is very motivated to learn and enjoys being in school.

Zhang, 13, 7th Grade Student from China

Zhang is a 13-year old who arrived to the U.S. from Fuzhou, China at the end of 5th grade. A Newcomer Emergent Bilingual in a stand-alone ENL class, he attends a large, urban middle school.

Zhang is a 13-year old who arrived to the U.S. from Fuzhou, China at the end of 5th grade. A Newcomer Emergent Bilingual in a stand-alone ENL class, he attends a large, urban middle school.

When he arrived from China, his teachers found Zhang to be quiet and reserved. He had taken some English at his school in China, yet struggled to understand all but very simple words and looked to Mandarin-speaking peers to help him communicate. In the last two years, however, as his teachers have invited Zhang to use whatever language he feels most comfortable with to help him accomplish classroom activities, he has come out of his shell, and has even experimented more with English.

Inviting Zhang to use Mandarin to accomplish classroom tasks also alerted teachers to his well-developed academic abilities in the language: he can write whole stories and essays with ease, and often reads novels in the language. Teachers encourage Zhang’s participation and continued academic growth by using web-based translation software to communicate their prompts and questions in subject area classes. Zhang also uses the web-based translation software on a class computer, for instance, when he responds to class tasks partially or wholly in Mandarin and translates them. His teachers also use Chinese-language texts, videos, and peers in the class to support Zhang as he develops English.

Zhang now does not shy away from speaking to classmates and teachers, even in English. He has also developed a great deal of confidence: at the end of 6th grade, he stood up in front of his social studies class and made an entire presentation in Mandarin about the Spartans and Athenians in Ancient Greece. While he still needs to use machine translation software for writing and when he doesn’t understand questions, Zhang tries to write as much as possible in English. Based on Zhang’s progress, his teachers are sure that he will reach the next level of English proficiency on the State exam by the end of 7th grade.

Helpful Links:

- Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL): Exemplary programs for Newcomer English language learners at the secondary level.

- City University of New York-New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals (CUNY-NYSIEB): Resources for work with particular subgroups.

- Colorín Colorado: Best Practices for ELLs: Peer-Assisted Learning.

- Colorín Colorado: Resources for Newcomer students.

- Hauser, B. (2012). The New Kids: Big Dreams and Brave Journeys at a High School for Immigrant Teens. New York, NY: Free Press.

- U.S. Department of Education: Newcomers Toolkit.

Further Reading and References:

Brooks, M.D. (2017). How and when did you learn your languages? Bilingual students’ linguistic

experiences and literacy instruction. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(4), 383-393.

Carhill-Poza, A. (2017). If you don’t find a friend in here, it’s gonna be hard for you: Structuring

bilingual peer support for language learning in urban high schools. Linguistics and

Education, 37, 63-72.

España, C. (2016). Bilingual matters: using technology to make education more accessible for

our emergent bilingual students. Literacy Today, 34(3), 26.

Fu, D. (2009). Writing between languages: How English language learners make the transition

to fluency, grades 4–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

García, O., Johnson, S.I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging

student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia: Caslon.

Gaytan, F.X., Carhill, A., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2007). Understanding and responding to the needs

of newcomer immigrant youth and families. The Prevention Researcher, 14(4), 10–14.

Haynes, J. (2007). Getting started with English language learners: How educators can meet the

challenge. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Zacrian, D. & Haynes, J. (2012). The Essential Guide for Educating Beginning English Learners.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Acknowledgments

This CUNY-NYSIEB resource was created by Kathryn Fangsrud Carpenter, Sara Vogel, and Tom Snell. Kate Seltzer and Maite Sánchez served as advisors to the authors. We would like to give special thanks to the teachers and administrators who provided feedback on this resource.

The bulletin board was changed monthly to feature a new set of words based on a theme, such as fruits, seasons, numbers, and colors. The teachers shared that their Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students loved helping create this board because it made them feel like experts with valuable knowledge to share with others, whose language was valuable within the community. Whenever the theme changed, the teachers always made sure to have an “unveiling ceremony,” when the kids would teach passerbys (teachers and administrators) how to pronounce the Mandarin words.

The bulletin board was changed monthly to feature a new set of words based on a theme, such as fruits, seasons, numbers, and colors. The teachers shared that their Newcomer Emergent Bilingual students loved helping create this board because it made them feel like experts with valuable knowledge to share with others, whose language was valuable within the community. Whenever the theme changed, the teachers always made sure to have an “unveiling ceremony,” when the kids would teach passerbys (teachers and administrators) how to pronounce the Mandarin words.