Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

Background information on Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE

Principles to Support Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE

Spotlight on Students: Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE

Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

Young people whose schooling in their home country has been interrupted or insufficient can arrive to U.S. schools in need of the language and literacy skills that will help them find academic success. These students, labeled Students with Interrupted/Inconsistent Formal Education (SIFE), may also be in need of grade-level content knowledge and basic school habits. As a teacher, you may find it challenging to meet all the diverse needs these students present. This resource is designed to help you in your work with and advocacy for this unique population of students.

The ideas and examples we will share in this resource draw on the expertise and years of experience of the CUNY-NYSIEB support team, whose members have guided dozens of schools across New York State to develop best practices for emergent bilingual (EBL) students, including those labeled SIFE. We draw on our core principles in all the work we do, which include viewing bilingualism as a resource in education and supporting a multilingual ecology for the whole school.

Before we start, a quick note about language: If you are new to CUNY-NYSIEB’s work, you may be wondering why we refer to students as we do. Labeling so often characterizes emergent bilinguals’ learning experiences in school: they are called ELLs (English Language Learners) or LEPs (Limited English Proficient), terms that emphasize what they can’t do or don’t have. We refer to these students as Emergent Bilinguals (EBLs) to emphasize their skills (bilingualism) and their growth potential (emergence).

I. Background Information on Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE

How do we get to know emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE?

Students with Interrupted or Inconsistent Education (SIFE) typically arrive in the U.S. with literacy and content skills that do not meet the standards held by schools. There are many reasons students may be labeled SIFE:

- Lack of schooling due to political or social circumstances in their home country

- Lack of availability of formal education beyond the early years in their home country

- Travel between the U.S. and their home country that has led to gaps in their education (DeCapua & Marshall, 2010).

Most students labeled as SIFE are additionally identified as Newcomers, meaning that they are recent arrivals to the U.S. and U.S. schools. You may also want to check out the CUNY-NYSIEB webpage on Newcomer students for more information on working with this population.

It is also important to realize that many students labeled as SIFE have specific social and psychological needs given traumatic migration experiences or lived experience with war or displacement. Some may also need assistance learning basic school routines, given their limited experience with formal schooling. Last, it is also common for these students to report feeling frustrated or isolated given how academically different they may be from their peers (Spaulding, Carolino & Amen, 2004). Because of these complex socio-emotional needs, many emergent bilinguals labeled as SIFE do not get the support they need and may eventually drop out of school (Spaulding, Carolino, & Amen, 2004).

What can schools do for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE?

Quality programs for SIFE not only address their educational needs, but also their complex social and emotional concerns. These programs can also serve to leverage the experiential knowledge these students bring, in order to promote and reinforce new content learning. While they may lack formal school skills, emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE do have a wealth of cultural, functional, and home language knowledge and experiences that can and should be treated as resources in classroom settings. Maintaining high expectations for these students and encouraging positive attitudes toward education can motivate them to continue learning and stay in school.

II. Using CUNY-NYSIEB Principles to Support Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE

In our experience working with schools, a few strategies have stood out as particularly promising for supporting emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE. In this section, we describe and highlight examples from CUNY-NYSIEB cohort schools where these strategies have been successfully implemented. We present them here divided into “school-based” and “classroom-based” practices, to differentiate between what we have seen successfully implemented on a schoolwide level and what individual teachers have accomplished with these students.

A. Supporting emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE on a schoolwide level

Because of the varied needs of emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, many schools see the immediate utility of creating a separate class for them in order to provide academic and language support. While this impulse is reasonable and can be beneficial, many schools either do not have the resources or the student numbers to do so. In addition, there is the risk that keeping students in specialized SIFE programs for longer than a few months to a year can limit their development of English and lead to feelings of social isolation (Carhill-Poza, 2017). There are many ways to support these students at your school, and we emphasize that the effort needs to be schoolwide. That is, whether or not you have a special program, the whole school community can adopt certain structures and attitudes that help support emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE holistically and set them up for future success. The following examples describe specific ways schools can support these students and help them cultivate a sense of ownership and belonging in the school environment.

1. Support services for students and families

When emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE arrive at your school, it is important to start getting to know them and their families so you can understand their unique needs. As we have discussed, many students who are considered SIFE experience trauma, or arrive in the U.S. under difficult circumstances. Their socio-emotional needs are a priority and specific interventions are needed to support them (Custodio & O’Loughlin, 2017). Getting to know their stories, where they come from, the language(s) they speak, and their cultural practices, can help you not only identify ways to support them and their families but also give a point of entry when it comes to planning an academic program (for more on a culturally relevant learning environment and pedagogy, see Celic and Seltzer, 2012).

Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE: Learning About Students’ Backgrounds

The “Initial Entry” chapter of the CUNY-NYSIEB Framework on the Education of Emergent Bilinguals with Low Home Literacy has helpful information on how to assess a student’s home and English language literacy, and how to get to know their family (see p. 5-6).

The New York State Department of Education has designed a number of helpful resources for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE. Two are here: SIFE Oral Interview Questionnaire and Guidance Document. These resources can help you to gather information about students who are potentially SIFE, learn about a student’s home and family background, educational history, and more. These resources are translated into 9 different languages.

Once you have a better grasp of the histories and background of your emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, you can take a few other basic steps to ensure they and their families are supported on a schoolwide level:

- Make guidance counselors aware of students’ histories and living situations.

- Involve families of emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE in any support plan for these students.

- Create a support group for students and families in similar situations (Auslander, 2016).

- Connect families to different social services and community organizations near and within your school.

- Reach out to organizations that can partner with your school.

Involving families and community members in decision-making and support structures for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE helps provide a holistic approach to their wellbeing and development. You should also consider forging partnerships with community support organizations that continue even after the students age out or graduate from school, so they can continue to receive support (WIDA Consortium, 2015; Advocates for Children, 2010).

2. Appropriate professional development for all staff members

When working with emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, it is critical to develop a culturally responsive pedagogy: a teaching and planning model grounded in the historical, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds of students. Either you can learn about your students on your own and with colleagues in professional learning communities, or you can ask your administration to provide opportunities for staff members working with emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE to learn about the students’ countries of origin, educational experiences, and cultural/linguistic practices. The more you know about students’ strengths, the more you can leverage and extend them. You should also try to learn all you can about second language acquisition, emergent literacy practices, and specialized instructional methods designed to accelerate the academic achievement of emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE SIFE (Advocates for Children, 2010; Mendenhall, Bartlett, & Ghaffar-Kucher, 2017; WIDA Consortium, 2015).

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Learning About Students’ Home Languages We have worked with numerous cohort schools on getting to know more about students’ home languages and cultures. This helps teachers understand students’ home languages practices and build on them. Particularly for students identified as SIFE, being able to make connections between what they know in their home language and what they are learning in school is critical for their academic success. Here is what some cohort teachers said after working to learn more about the home languages of their students identified as SIFE:

- “Knowing about students’ home languages helps me understand why students use certain sentence structures in English” (Middle school bilingual teacher) (See Syntax Transfer, p. 176 of the Translanguaging Guide)

- “At the start of each unit, I create a reference chart to display key vocabulary in both English and the home language. If I can’t pronounce the words, or if my dictionary is wrong, the students tell me and I correct it!” (Middle school ELA teacher) (See Multilingual Word Walls, p. 147, and Vocabulary Inquiry Across Languages, p. 165, of the Translanguaging Guide)

- “I have built up a library of home language resources relating to the topics I teach, based on what I know about the languages spoken by students in my class.If they need to do research or build understanding of a topic, I have somewhere to direct them.” (High school ENL teacher) (See A Multilingual Learning Environment, p. 20, and Using Multilingual Texts, p. 81, of the Translanguaging Guide)

The CUNY-NYSIEB Languages of New York State Guide for Educators shares information about the 11 languages most commonly spoken by students in New York State. The syntax, common phrases, history, and context of each language are described chapter by chapter. You may find this guide useful in conjunction with the Translanguaging Guide as you plan lessons that use your students’ home languages as resources for learning.

The CUNY-NYSIEB Languages of New York State Guide for Educators shares information about the 11 languages most commonly spoken by students in New York State. The syntax, common phrases, history, and context of each language are described chapter by chapter. You may find this guide useful in conjunction with the Translanguaging Guide as you plan lessons that use your students’ home languages as resources for learning.

3. Creating sheltered programs

Learning a new school system can be overwhelming for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, who are also adjusting to a new country and learning a new language. Especially for adolescents, who travel between classrooms and teachers, and for whom academic demands are higher, adjustment can be especially difficult. Students are often be more successful in a sheltered program with dedicated classes specifically designed to meet their language, literacy, academic, socio-cultural, and emotional needs. This is particularly important for students with low literacy, who are some of the most at-risk students in middle and high school classrooms (Custodio & O’Loughlin, 2017). With this said, sheltered programs should be only a temporary setting for these students: emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE who are kept in sheltered programs longer than 6 months to one year can end up isolated from their peers, which can have an impact on their English language development (Carhill-Poza, 2017).

Sheltered SIFE Program Model: Bridges to Academic Success

Bridges to Academic Success (Bridges) is a highly successful sheltered instruction program for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE. Designed as an approximately one-year intervention, the program targets recently arrived teens who are new to English and have no higher than a 3rd grade literacy level in their home language. The program recognizes that while these students may not have been exposed to the academic content and ways of thinking expected of students in U.S. secondary schools, they arrive with a wealth of knowledge and experience. For instance, many of them have learned primarily through listening and speaking, so have well-developed oral language. However, not even these experiences have prepared them for the academic demands of U.S. secondary classrooms where texts are used as resources to learn.

In the Bridges program, students attend a sheltered program at their school, with dedicated classes designed to meet their language, literacy, academic, socio-cultural and emotional needs. The Bridges curriculum was developed for a multilingual context to build on the rich and unique life experiences students bring to the classroom, and to target the foundational language and literacy skills and background content knowledge students will need to participate meaningfully in mainstream secondary classrooms. Teachers in the program also receive training in the characteristics of emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE so they can be more sensitive and culturally responsive.

The Bridges program has been successfully implemented in several high schools across New York State. For more information, see the Bridges to Academic Success website.

4. Collaboration across content areas

If your school cannot create and sustain a sheltered program for emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, an alternative is to create collaboration models across academic departments. When teachers collaborate across the curriculum, emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE are supported as they develop content knowledge, language for academic purposes, and literacy skills. This is especially important in middle and high schools, where each subject area has a separate instructional period. Administrators can organize regular planning times so that teachers in the content areas can integrate language instruction into all subject areas to help students advance to more advanced literacy (Custodio & O’Laughlin, 2017; De Capua, Smathers, & Tang, 2009). You should also find ways to build on students’ home language practices throughout all classes. Because the academic skills students acquire in their home languages can be extended to similar skills in their additional language (Goldenberg, 2008), what students learn in their home language will promote higher levels of scholastic and reading achievement in English (August & Shanahan, 2006).

The CUNY-NYSIEB Framework for the Education of Emergent Bilinguals with Low Home Literacy we referenced earlier is also a great resource for learning about how to design and implement a successful program for students labeled SIFE. It takes into account programmatic structures and pedagogical practices, curricular structures and classroom resources. Revisit chapters 2 and 4 for specific information relating to collaborating across content areas.

B. Supporting emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE in the Classroom

For students new to both English and school environments, building on what they know and can do in their home language is crucial. When these students can engage in translanguaging, that is, use all of their language practices to learn, they are able to use the full range of their abilities and acquire language and content skills more quickly and easily. This is especially important for students who may have limited experience in classroom settings, because it allows them to use their strongest asset – their oral home language – to learn and practice school language and skills.

1. Integrating language instruction across content areas

Emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE need to build both literacy and academic skills, so it is important that schools integrate language instruction into all subject areas. For example, students can use oral language to build understandings about content area topics, generate ideas for writing, and build background knowledge before reading a text. When they learn to do this across the curriculum, students eventually learn to use texts as resources to build conceptual knowledge (Marshall, DeCapua, & Antolini, 2010). It is very important to stress that when emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE are using oral language to learn, this naturally will include home language practices. In a classroom context, making sure emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE can use and develop their entire linguistic repertoire is critical, in particular when they are making sense of new concepts (Kibler, 2010; Menken, 2013).

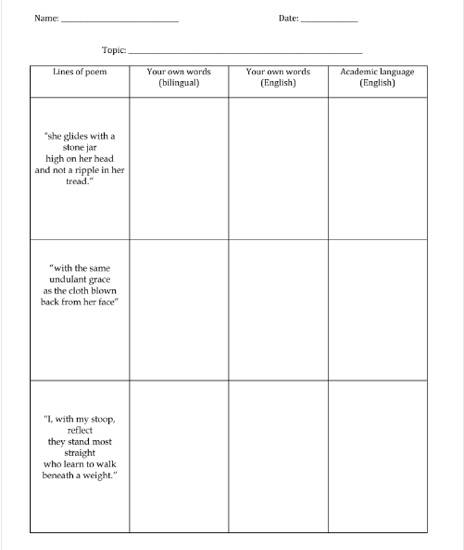

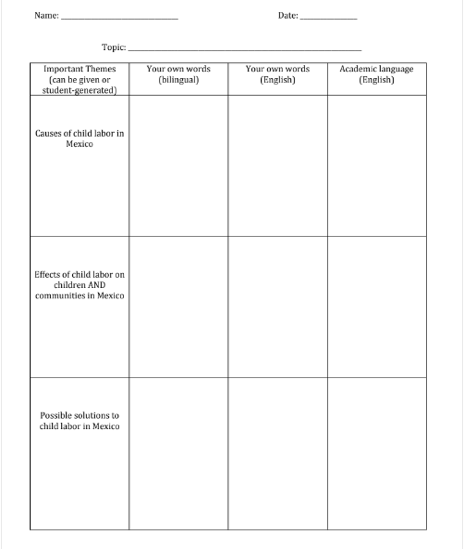

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Integrating Language Instruction Across Content Areas At one high school, teachers and CUNY-NYSIEB support staff designed and implemented one specific strategy across grade levels and content-areas to help emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE acquire academic English skills by building on oral language and emergent literacy skills in their home language. The strategy was a graphic organizer (see images below), where students would first take notes in the home language or bilingually (column 1), and then work with a partner to translate their ideas into English (column 2). Subsequently, the teacher would build on their uses of English and the home language by introducing key concept words and language structures aligned with content-specific goals (column 3). When they met in grade level cohorts, and with CUNY-NYSIEB support staff, teachers noted how the strategy helped their students feel more prepared to engage in class activities, improved homework completion rates, and supported them to be active participants in group work. The following examples show how different teachers at the school implemented the strategy; the first is a social studies class and the second is an ELA/ENL class:

Social Studies: Building background on a theme ELA/ENL: Responding to poetry Successful uses of translanguaging strategies to integrate language and content include:

- Use of home language to scaffold learning across content areas

- Multilingual graphic organizers

- Multilingual partner work

Click here to download an editable sample of this academic language scaffolding tool.

2. Fostering collaboration.

Learning to work collaboratively with others is critical to emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE. They can use peers to help negotiate and understand new concepts, practice new language, tackle difficult texts, and more. Also, small group work provides an opportunity for students to express their ideas in a lower risk environment (Marshall, DeCapua, & Antolini, 2010; Walqui, 2006). They can learn structures for collaboration and use both the new and home languages in learning activities, without fears of being judged or misunderstood.

In order for collaboration to be effective, all students – but especially emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE – need to be taught the interpersonal skills needed to interact with one another in groups, such as turn taking, using encouraging language, providing feedback, and building on each other’s ideas. Students newer to the country and newer to English may benefit from language stems (i.e. sentence starters)) or observing their peers model accountable talk (for instance in a “fishbowl” activity).

Some of our cohort schools have also found it highly beneficial to assign “buddies” to emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE. These buddies, who ideally would speak the home language of the peer they are paired with, are helpful to students when they have questions about school routines or a classroom assignment or concept, and can act as role models for recently arrived students who might feel overwhelmed by the academic demands of the U.S. educational system (Sánchez, Espinet, & Seltzer, 2014).

3. Activating prior knowledge

Helping all students, and particularly emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE, activate prior knowledge allows them to make more meaningful connections to their new content and language learning, especially when you use texts, approaches, and themes that are culturally relevant. Drawing from familiar experiences provides a bridge to new concepts and academic language, and building from what students already know helps to balance the cognitive load (Walqui, 2006).

It is also critical to realize that for many students known as SIFE, prior learning experiences have been based on oral language, which flows directly from experience. This means that these students likely have mainly learned by doing, where someone has explained a procedure to them step-by-step that has a concrete application. This is a very different way of learning than the analytical tasks and text-based learning decontextualized from real-world experience that is prevalent in U.S. schools (Marshall, DeCapua, & Antolini, 2010). Whenever possible, you should provide hands-on learning experiences, encourage these students to use oral language (home language and new language/English), and make explicit connection to new learning and past experiences in order to help them connect to their prior knowledge and extend their learning.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Translanguaging to Activate Prior Knowledge At one CUNY-NYSIEB cohort school, an ENL teacher had three recently-arrived emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE: two from Haiti and one from Mexico. To launch a unit exploring the theme of community, the curriculum required the teacher to show a picture of a small town in the United States, in a valley surrounded by trees. She realized that her students would have a hard time making personal connections to this narrow definition of community, so she looked up pictures of different settings in Haiti, Mexico, and the neighborhood around the school. The students viewed the photographs, then worked with language partners to discuss what makes a community, using their home languages and sentence starters in English to complete a short response in English. She also provided cognates for the key words, and had students do a noticing activity about the similarities in the terms: community / comunidad (Spanish) / kominote (Haitian Creole). Not only were students able to describe what community meant to them after this activity, they were also visibly excited to see communities that looked like the ones they came from. Even her Mexican-American students were excited to see the country their families had shared with them so often in pictures or on vacations.

Successful uses of translanguaging strategies to activate prior knowledge included:

- Culturally relevant images to spark prior knowledge

- Home language turn-and-talk to build prior knowledge with language partners

- A focus on English/home language cognates for major unit vocabulary

- Oral language used to prepare for written output

Note: Similar examples are described in the CUNY-NYSIEB Framework for Students with Low Home Literacy

4. Spotlight on Classroom Practices: Translanguaging and SIFE Students

| Translanguaging in Action for SIFE: Thematic Study of Immigration |

| The following description shares how one cohort school incorporated many of the ideas for supporting students identified as SIFE we have described in this brief. At the end of the description, the ideas are highlighted for your reference. For more strategies, please see the CUNY-NYSIEB Translanguaging Guide.

For an end of the year social studies unit on immigration, one cohort school worked to develop multiple supports for their students identified as SIFE. In the beginning of the unit, students used the home language to “interview” each other about their own stories, and reflected on each others’ experiences. They used these skills to write interview questions in English and interview community volunteers about immigration/their immigrant experience. Additionally, parents and community members were invited into the school to discuss their “coming to America” stories with the students, in the students’ home language (at this particular school, they were all Spanish-speaking). Students used a bilingual graphic organizer to take notes as they listened, and discussed their impressions of the stories in Spanish. They also watched clips from a Spanish-language film about a Mexican boy who immigrates to the U.S. to find his mother (La Misma Luna, Under the Same Moon). Subsequent to all of these experiences, students wrote summaries and a response to what they had learned in English. Also throughout this phase, the teachers made sure to build a bank of relevant vocabulary words for the students, in both English and Spanish. Once students had build this background knowledge and unit vocabulary, they began to read the course texts (My Diary from Here to There– an immigration story also available in bilingual edition) and historical documents relating to immigration in the U.S. They also took a class field trip to Ellis Island. The culminating project of this unit was a series of vignettes in English the students produced from the different interviews and historical research they did. The school’s technology integrator worked with teachers and students to create a secure website where the students uploaded their written work, pictures, and videos. Parents were invited in at the end of the year for a celebration of the students work, or “showcase” of the final website.

Successful uses of translanguaging strategies in this unit include:

|

Spotlight on Students: SIFE

Josue, 14, 7th grade student from the Dominican Republic

Josue is a 14 year-old who arrived to New York City from the Dominican Republic and was placed in 7th grade. He was identified not only as a Newcomer but also as SIFE because he lived in a rural area in the Dominican Republic, and although attended school, he was reading at a 2nd grade level in Spanish, his home language. He had never studied in English before coming to the U.S.

When he arrived, Josue was placed in his school’s Spanish-English Transitional Bilingual Education program. Josue is comfortable expressing his ideas orally in Spanish, and his thinking and ideas are very complex. However, he struggles with academic vocabulary and with communicating his ideas in writing. Since he often writes in fragments, his teachers are teaching him strategies to make full sentences. He is also a wonderful artist, and often uses drawing to express his ideas where words fail him.

Josue has also struggled to make sense of certain school-based genres. For example, the first time that he encountered multiple choice questions, he circled all the answers. The school has provided academic intervention support services where he is learning basic school skills, such as organizing his folder. As he has started to make sense of what is expected of him in school, his literacy skills both in Spanish and English have become stronger. Since he grew up in the countryside, he also has knowledge that students in the city don’t have and he loves sharing his experiences during class.

Wilson, 17, 10th grade student from Haiti

Wilson is a 17 year-old who arrived from Haiti and was placed in the 10th grade. He was identified not only as a Newcomer but also as SIFE because his schooling had been disrupted by the earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010. He was reading at a 1st grade level in Haitian-Creole, his home language, and had never studied in English before coming to the U.S.

Wilson attends high school in a large city in New York where he has been placed in the stand-alone English as a New Language (ENL) program. When Wilson first arrived, he was very quiet and observant. He quickly learned basic school routines but was very reluctant to engage in any kind of group work, preferring instead to work individually. He was paired with students from Haiti so they could provide him with peer support. The other Haitian students in his class have had their schooling in French, so they are able to make connections between academic language in French and English, but since Wilson doesn’t speak French, it is sometimes a challenge for them to help him.

From the beginning, Wilson was always willing to follow directions. He is very eager to work hard even though it is difficult for him to complete some of his school assignments. Since he is still developing his literacy for academic purposes, his ENL teacher scaffolds his work so he is able to participate. For example, at the beginning of the year, she encouraged him to draw his responses to questions. As he learned more English, he was able to use simple words and sentences to caption his drawings. In his first year in high school, he has been able to learn basic conversational English and he is very determined to continue to learn.

Nazir, 16, 9th grade student from Yemen

Nazir is a 16 year-old who arrived from Yemen and was placed in 9th grade. He was identified as SIFE because he lived and worked in a rural area of Yemen and had limited opportunities for formal schooling. Nazir attends high school in a large city in Western New York, where he has been placed in a stand-alone English as a New Language (ENL) program. When he first entered high school, he was unfamiliar with basic school routines, and he was overwhelmed by being in a new setting. He spent much of his class time doodling and writing his name on his folder. His school programs 9th and 10th grade students together, so the 10th graders can provide peer language support to the newcomer 9th graders. Upon his entrance to the school, he was paired with Arabic-speaking students so that they could help him understand how to navigate the classroom and school routines. He also received small-group English literacy support.

Nazir is a very friendly and social student. Despite the fact that he started in 9th grade with almost no English, he has made friends with students who speak different languages and come from many cultures. He loves to play soccer and talk about it. This has been a common ground for him to socialize with kids from a variety of backgrounds. Because of his social skills, Nazir’s English oral language has developed very quickly and he was able to communicate orally in English early on. Since many of his friends are from Latin American countries, he has also learned some Spanish.

Nazir is now able to understand the routines of the class and to use them to his advantage. He thrives doing group work and takes a leadership role in organizing his group and getting everyone to focus. Working in a group helps Nazir because it provides a venue for him to participate in the class and check his understanding with other students. The school’s philosophy is to encourage students to use their home language for learning English and to work in small groups of students who share a home language. While he is making significant progress, Nazir does continue to struggles to conceptualize what he is supposed to do in his class work, particularly if an activity has more than one component.

Whether you are teachers, teacher leaders, or administrators, we hope that the ideas outlined here can prove helpful to you and your colleagues in your work with emergent bilingual students labeled SIFE. For more information on translanguaging and special populations, please visit our website or refer to some of the links and resources below.

Want more? Here are some Helpful Links:

- CUNY-NYSIEB Framework for Students with Low Home Literacy: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide that takes into account programmatic structures, pedagogical practices, curricular structures, and classroom resources. It consists of a set of six recommendations on educating emergent bilinguals labeled SIFE that should be adapted with flexibility to meet the specific needs and strengths of the students, the educators, and the school.

- NYSED SIFE Website: Provides background on emergent bilinguals labeled as SIFE, describes the screening process for these students, and links to the screening tools.

- Multilingual Literacy Screener: A multilingual screening tool used to inform teachers and administrators of emergent bilinguals labeled as SIFE students’ reading and math skills in the home language. To access this resource, refer to the Quick Sheet and prior to administration you should review the user manual and may want to view the webinar on how to administer the screener.

- Writing Screener: Available in English and 9 languages spoken by emergent bilinguals labeled as SIFE, this tool provides a quick way to assess students’ basic writing skills in their home language.

- Colorín Colorado on Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled SIFE: Provides an overview of where emergent bilinguals labeled as SIFE come from and what languages they speak, their unique needs, and helpful hints on providing school-wide support for them.

Additional Resources and Works Cited:

Advocates for Children of New York. (2010). Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE): A Challenge for the New York City Public Schools. Available at http://www.advocatesforchildren.org/sites/default/files/library/sife_2010.pdf?pt=1

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language minority children and youth. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Auslander, L. (2016, September). The role of academic inquiry and culturally responsive instruction in promoting learning for multilingual students. Presentation at The Multilingual and Language Empowerment Symposium: A Response to Inequality. The CUNY Graduate Center, New York, NY.

Bridges to Academic Success (N.D.). SIFE Project: Curriculum Overview. Available at http://bridges-sifeproject.com/program-overview/

Carhill-Poza, A. (2017). If you don’t find a friend in here, it’s gonna be hard for you: Structuring bilingual peer support for language learning in urban high schools. Linguistics and Education, 37, 63-72.

Celic, C., & Seltzer, K. (2012). Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators. New York: CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Retrieved from http://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf

Custodio, B., & O’Loughlin, J. B. (2017). Students with interrupted formal education: Bridging where they are and what they need. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

DeCapua, A., & Marshall, H. W. (2010). Students with limited or interrupted formal education in U.S. classrooms. The Urban Review, 42(2), 159-173.

DeCapua, A., Smathers, W., & Tang, L. F. (2009). Meeting the needs of students with limited or interrupted schooling: A guide for educators. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Goldenberg. C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 8–44.

Kibler, A. (2010). Writing through two languages: First language expertise in a language minority classroom. Journal of Second Language Writing19, 121–142.

Klein, E. C. & Martohardjono, G. (2009). Understanding the Student with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE) Phase II: A study of SIFE skills, needs and achievement. Report to the New York City Department of Education.

Marshall, H. W., DeCapua, A., & Antolini, C. (2010). Engaging English language learners with limited or interrupted formal education. Educator’s Voice,3, 56-65.

Mendenhall, M., Bartlett, L., & Ghaffar-Kucher, A. (2017). “If you need help, they are always there for us:” Education for refugees in an international high school in NYC. Urban Review 49, 1–25.

Sánchez, M.T., Espinet, I., & Seltzer, K. (2014). Supporting Emergent Bilinguals in New York: Understanding Successful School Practices. New York: CUNY-NYSIEB. Retrieved from http://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CUNY-NYSIEB-Contemporary-Report-Full-Feb-Final.pdf

Spaulding, S., Carolino, B., & Amen, K. (Jan 2004). Immigrant Students and Secondary School Reform: Compendium of Best Practices. Washington, DC: CCSSO. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED484705.pdf

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 159-180.

WIDA Consortium. (2015). WIDA focus on: SLIFE: Students with limited or interrupted formal education. Retrieved on May 30, 2017 from, http://www.njtesol-njbe.org/handouts15/WIDA_Focus_on_SLIFE.pdf

Acknowledgments

This CUNY-NYSIEB resource was created by Kathryn Fangsrud Carpenter, Ivana Espinet, and Lisa Auslander. Maite Sánchez and Kate Seltzer served as advisors to the authors. We would like to give special thanks to the teachers and administrators who provided feedback on this resource.