Supporting Young Emergent Bilinguals: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

Background information on Young Emergent Bilinguals

Using CUNY-NYSIEB Principles to Support Young Emergent Bilinguals

Supporting Young Emergent Bilinguals: Tips from CUNY-NYSIEB

Young children with home or primary languages other than English (LOTEs) enter nurseries, pre-school, and kindergarten settings withemergent language repertoires that educators must recognize. These students, whom we refer to as young emergent bilinguals, or Emergent Multilingual Learners (EMLLs), arenot just developing emergent English skills— they are becoming multilingual and multiliterate. As teachers, we can find it challenging to learn about, sustain, and build upon young children’s emergent multilingualism, especially if we do not speak their home languages. This resource is meant to help you understand, educate, and advocate for this student population.

The ideas and examples we share in this resource draw on the expertise and years of experience of the CUNY-NYSIEB support team, whose members have guided dozens of schools across New York State to develop best practices for Emergent Bilingual students, including those in early childhood programs. We draw on our core principles in all the work we do, which view bilingualism as a resource in education and support a multilingual ecology for the whole school.

Before we start, a quick note about language: If you are new to CUNY-NYSIEB’s work, you may be wondering why we refer to students as we do. Labeling so often characterizes emergent bilinguals’ learning experiences in school: they are called ELLs (English Language Learners), and in the case of those IEPs, SWDs (Students with Disabilities) or SPEDs (Special Education Students), all terms that emphasize what they can’t do or the services they receive. We refer to these students as emergent bilinguals to emphasize their skills (bilingualism) and their growth potential (emergence).

I. Background Information on Young Emergent Bilinguals

How do we get to know Young Emergent Bilinguals?

Young emergent bilinguals are children from infancy to 2nd grade who are socialized in homes in which both English and a language other than English are heard. In some cases, the parents and/or siblings are bilingual themselves. In other cases, the parents only speak a language other than English, but children hear English on the television, the radio, and in the surrounding community. Because children are very young, they are developing both English and their home language simultaneously. These children usually enter school with receptive abilities that are typically more developed than their productive performances in either language.

What should teachers understand about the language of young emergent bilinguals? There is No “Gap” in the Language of Young Emergent Bilinguals

While it is true that the language practices of multilingual children differ from those of monolingual children, we must recognize that the idea of a “language gap” is a fallacy. This “gap”, which aims to describe the alleged disparity in vocabulary that students from underprivileged backgrounds enter school with (mostly bilingual and bidialectal children of color), is based on deficit views of marginalized communities. Their linguistic practices are stigmatized and seen as impoverished because the language practices of privileged monolingual communities have been extensively normalized (García & Otheguy, 2016). Educators must understand that young emergent bilinguals language in ways that are richer and more complex than the language typically recognized in schools.Young Emergent Bilingual Children Translanguage Naturally

Bilingual infants experience language bilingually so, unlike monolinguals, they produce language bilingually when they begin to babble. Although parents recognize their initial sounds as attempts to say words in specific languages, young multilingual children deploy all of their language features freely, or translanguage, before they begin to realize that it is perceived as deficient by many adults. A 14-month-old’s words, for example, might include “agua,” “meow-meow” “milk,” “guagua,” “bus,” and “choo-choo”. Her words, accompanied by other meaning-making resources, such as gestures, pulling, crying, and onomatopoeic words, are meaningful and must be validated by those with whom she interacts, including her teachers.The Language of Young Emergent Bilingual Children is Multimodal

Like all young children, the language of Emergent Multilingual Learners is multimodal. That is, young children use gestures, point, act, draw, sing, sign, and find numerous ways to communicate and make meaning. Therefore, many of the language practices young children use to play, ask and answer questions, tell a story, express feelings, and solve problems go beyond what many adults regard as language. Educators must validate the rich and organic multimodal language of young children before they can extend them.

What Can Early Childhood Programs do for Emergent Multilingual Learners?

Young emergent bilingual children flourish in early childhood programs that engage all of their linguistic and cultural identities. Educators should welcome their emergent multilingualism by creating spaces within their classrooms for bilingual languaging, bilingual literacy experiences, and bilingual play. In order to understand, validate, and extend a child’s bilingualism, educators must maintain strong partnerships with their parents and families.

II. Using CUNY-NYSIEB Principles to Support Emergent Bilinguals in Early Childhood

In our experience working with schools, a few strategies have stood out as particularly promising for young emergent bilinguals in early childhood programs. Below, we highlight classroom examples from CUNY-NYSIEB cohort schools where these strategies have been successfully implemented. We distinguish between “school-based” and “classroom-based” practices, to differentiate between what we have seen successfully implemented on a schoolwide level and what individual teachers have accomplished with these students.

A. Supporting Young Emergent Bilinguals on a Schoolwide Level

Learn with and from families

Strong partnerships with parents and families are crucial for the success young emergent bilingual children. Schools should cultivate an environment where parents feel welcomed and are often reminded of the importance of continuing to develop their child’s home language(s). It is also important to encourage family participation in schoolwide decision-making, moving beyond a mere family “involvement” paradigm to instead consider meaningful family engagement or even family leadership in schools (Menken, 2017). These collaborations need to be regular and ongoing throughout the year, not just seen as special enhancements to instruction.

Allotting time for teachers to learn with and from families of is essential. Families have a wealth of language and knowledge that can enrich the learning experience of all of the school community. Successful partnerships require educators to spend time talking to parents, learning about their social histories, their interactions, and their language/literacy use. Some schools organize orientations, community events, open-school days, and other opportunities for families to lead events and share their hobbies, interests, and backgrounds. Educators can also get to know families through in-person meetings, phone calls, or even home visits. Some questions that teachers in our cohort schools have asked to learn more about their young multilingual students and their families include:

- How would you describe your child?

- What family members are in your child’s life?

- What do your family members do for a living?

- What does your child enjoy doing on the weekends?

- What are some of your family’s favorite television shows? (In which languages?)

- What variety of texts does your family have in your home? (i.e., books, newspapers, bibles, etc.) (Languages?)

- Can you share some of your child’s experiences with books and oral stories?

- Do you share nursery rhymes and/or games from your own socio-cultural backgrounds with your child?

- What genres does your family enjoy reading?

- Can you think of the different purposes reading and writing play in your lives? (i.e., shopping lists, prayers, etc.) (Languages?)

- What does your child enjoy playing? With whom? (In which languages?)

- Does your child use the internet or any digital/online games? (In which languages?)

- What else is your child interested in?

- Is there anything else that you would like to share with us about your child?

- Would you feel comfortable sharing your hobbies/skills/talents/interests with our class community?

Questions to Learn About Families’ Linguistic Backgrounds:

- What languages do your family members speak at home?

- In what language do you speak to your child most of the time?

- What languages does your child understand?

- In what language does your child speak to you… to others?

- What are some ways your child uses gestures or objects to communicate?

- In what language does your child attempt to read/write?

- In what languages do you sing, read, or tell stories to your child?

- How has your child learned English so far (television shows, siblings, childcare, etc.)?

For more intake questions and ideas about getting to know multilingual children of early childhood ages, see “Right from the Start: A Protocol for Identifying and Planning Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals in Universal Prekindergarten”.

Professional Development and Collaborative Planning for Teachers

Ongoing schoolwide support is imperative for educators to leverage young children’s emerging bilingualism to enhance their learning. Teachers benefit from time and space for collaborative inquiry and planning that allows them to share expertise and reflect on their students’ multilingual practices.

In one of our cohort schools, early childhood teachers organized a Professional Learning Community (PLC) around play and bilingualism. Teachers met once a week to share anecdotes, ideas, and challenges around play-based instruction that welcomes and builds on students’ bilingualism. This collaborative space allowed the teachers to reflect on their own learning and implement new approaches in their classrooms.

For a guide to developing a PLC around early childhood and bilingualism, see our resource, “Professional Learning Community on Early Childhood Education and Bilingualism”.

B. Supporting Young Emergent Bilinguals at the Early Childhood Classroom Level

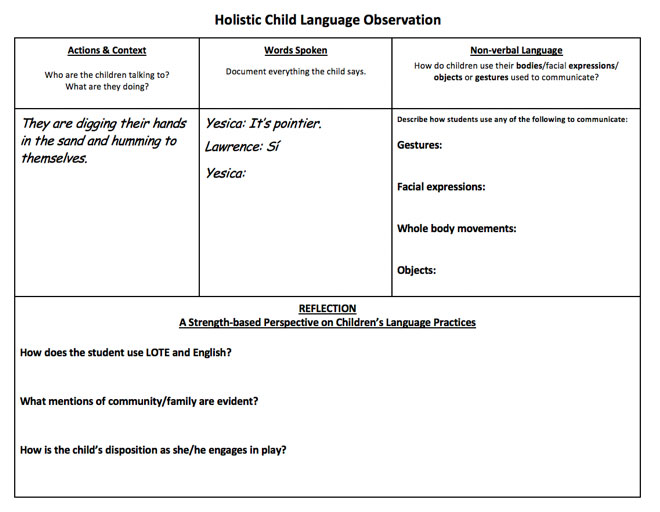

Holistically observe the language practices of young emergent bilinguals

To better understand and support the language development of young emergent bilinguals, teachers must observe them holistically and from a perspective of strength. This means that rather than focusing on the absence of specific words or attending to what is “appropriate” in one language or another, educators must focus on the messageof each interaction and the way students use all of their language (verbal and non-verbal) to express themselves and make meaning.

Educators can gain a broader perspective of multilingual children’s linguistic repertoires by observing each child in various contexts and taking note of how and when the child interacts with others. Such continuous and holistic observations allow teachers to design ways of validating and extending the linguistic repertoires of young emergent bilinguals.

CUNY NYSIEB’s Child Language Observation Protocol can guide educators in observing the language of Emergent Multilingual Learners holistically.

Validate, nurture, and extend young bilingual children’s language practices

Young emergent multilingual children enter early childhood classrooms with creative, flexible, and multimodal linguistic repertoires that are reflective of their lived experiences outside of the classroom. Their emergent language practices must be validated and celebrated before they are extended to help them meet expectations in contexts outside of the home. Teachers can understand, welcome, and build upon children’s full linguistic repertoire in creative and authentic ways throughout each day, even if they are not familiar with a child’s home language practices.

Build and sustain meaningful partnerships with families of Emergent Multilingual Learners

Parental partnerships should be commonplace, rather than a special enhancement to early childhood instruction. Regular and ongoing collaborations with families of young emergent bilinguals are especially fundamental, since cultural and linguistic differences often increase the distance between school and home. Parents who speak languages other than English often believe that they don’t have the language, knowledge, or skills that are valued in schools. Inviting families to share their cultural and linguistic backgrounds, as well as their interests and skills with the school community (i.e., storytelling, cooking, drawing, singing, planting, knitting) is a powerful way of reminding them that their wealth of language and knowledge is valuable and that they are their child’s primary educators—both in and out of the classroom. Phone conversations, audio and video recordings, and mobile applications are some creative and convenient ways to collaborate with families from afar.

Enhance play centers in ways that build on and sustain multilingualism

Young children develop language and learn about the world through play. During play, children feel safe to use their entire multimodal linguistic repertoire as they language freely and explore new ideas. For this reason, play is an opportunity to observe, welcome, and build on young children’s emergent multilingualism. Teachers can maximize young bilingual students’ learning and language development by creating opportunities for their bilingual imaginations to flourish during play.

To celebrate and build on students’ bilingualism during play, educators can:

- Label and refer to play centers in the different languages of the class.

- Allow children the freedom to choose where they want to play.

- Add toys and objects that reflect the diverse cultures and home languages of the class. Families can be asked to assist in selecting pretend foods, dress-up clothing, and playthings that encourage children to share their cultures and languages as they play.

- Model enthusiasm and interest in the diverse multimodal language practices that children exhibit as they play.

- Ask purposeful questions to better understand students’ language practices, and to support their bilingual development.

- To expand children’s linguistic repertoires, highlight different ways in which children use language during play and model other ways of using language to socialize, inquire, express feelings, and solve problems.

- Provide access to other resources such as audio, video, realia, and manipulatives, that support multimodal learning and translanguaging.

- Invite parents to play with students and share their multicultural and multilingual imaginations.

- Cultivate bilingual reading identities by extending children’s favorite books to play centers (see below).

For more about modeled play and purposefully-framed play, read Play-based Learning and Intentional Teaching: Forever Different? by Susan Edwards.

Foster bilingual reading identities

As educators engage young children in emergent literacy activities, it’s essential that they maintain their bilingual identities at the forefront of their learning. Educators should:

Read culturally and linguistically sustaining books

Thoughtful selection of culturally and linguistically sustaining books allows children to connect to literature, engage their bilingual imaginations, and begin to develop identities as bilingual readers. These include books written in students’ home languages, stories with characters who translanguage, texts that highlight children’s cultures, and books that tell everyday stories of diverse characters (for lists of such texts, see CUNY-NYSIEB’s Culturally Relevant Books and Resources).

Elicit multicultural and multilingual interpretations of books

Educators can also cultivate bilingual reading identities by engaging children’s bilingual imaginations when reading traditional storybooks like Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Teachers should encourage young children to use their unique multicultural and multilingual perspectives to interpret and reimagine stories. Adding book-related and culturally-relevant props to play areas is one way to promote multilingual interpretations of books. Families should be invited to assist in selecting pretend foods, dress-up clothing, and playthings that may encourage children to transform stories in ways that reflect their dynamic multilingual worlds.

Recommended

Recommended Children’s Books and Music for Early Childhood

Helpful Links:

Center for Linguistic and Cultural Democracy

Emergent Multilingual Learners in Prekindergarten Programs (NYSED)

Emergent Multilingual Learners Profile Process (NYSED)

Emergent Multilingual Learners Language Profile (NYSED)

Language Development & Play in Preschool – VIDEO by Teacher Scott Harding at Maury Elementary School, DC Public Schools.

iTEO: Examining the use of the App iTEO for teaching and learning languages in preschools and primary schools. (Research by professor Claudine Kirsch (PI)

NAEYC Position Statement: Where we Stand on Responding to Linguistic and Cultural Diversity

We Need Diverse Books — A non-profit and grassroots organization committed to diversity in children’s books.

Further Reading and References:

Axelrod, Y. (2017). “Ganchulinas” and “Rainbowli” Colors: Young Multilingual Children Play with Language in Head Start Classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal (45), 1, pp. 103-110.

Edwards, S. (June 2017). Play-based Learning and Intentional Teaching: Forever Different Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2).

Espinosa, C. and Lehner-Quam, A. (To be published 2019). Sustaining Bilingualism: Multimodal Arts Experiences for Young Readers and Writers. Language Arts.

García, O. and Otheguy, R. 2016). Interrogating the Language Gap of Young Bilingual and Bidialectal Students. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(1), pp. 52-65.

Genesee, F. (2015). Myths about early childhood bilingualism. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 56(1), 6-15.

Halgunseth, L. (2009). Family engagement, diverse families, and early childhood education programs: An integrated review of the literature. YC Young Children, 64(5), 56.

Gort, M. (2012). Code-switching patterns in the writing-related talk of young emergent bilinguals. Journal of Literacy Research, 44(1), pp. 45-75.

Kultti, A. & Pramling, N. (2017). Translation activities in bilingual early childhood education: Children’s perspectives and teachers’ scaffolding . Multilingual Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 36(6), pp. 703-725.

Maldonado, N. & Espinosa, C. (2012) Thinking and Speaking: Enhancing Oral Language Development in Emergent Bilingual Children’s Play Experiences. IPAUSA journal, pp. 31-37.

McLeod, S., Verdon, S. & Theobald, M. (2015). Becoming Bilingual: Children’s Insights About Making Friends in Bilingual Settings. International Journal of Early Childhood, (45), 3, pp 385-401.

Morell, Z. (2017). Rethinking Preschool Education through Bilingual Universal Pre-kindergarten: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Multilingual Education Research, 7(2).

Pontier, R. & Gort, M. (2016). Coordinated Translanguaging Pedagogy as Distributed Cognition: A Case Study of Two Dual Language Bilingual Education Preschool Coteachers’ Languaging Practices During Shared Book Readings, International Multilingual Research Journal, 10:2, 89-106.

Reyes, I., DaSilva Iddings A. C. & Feller, N. (2015). Promoting a Funds of Knowledge Perspective: Preservice Teachers’ Understanding about Language and Literacy Development of Preschool Emergent Bilinguals through Family and Community Interactions. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15(2) 1-26.

Rodriguez, M. (2015). Families and Educators Supporting Bilingualism in Early childhood. School Community Journal, (25), 2, 177-914 — http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx

Schwartz, M., Moin, V., & Leikin, M. (2011). Parents’ discourses about language strategies for their children’s preschool bilingual development. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education: An International Journal, 53(3), 149–166.

Schwartz, M. & Yagmur, K. (2018) Early language development and education: teachers, parents and children as agents. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 31:3, 215-219.

Soltero-Gonzalez, L. and Butvilofsky, S. (2015). The early Spanish and English writing development of simultaneous bilingual preschoolers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. (16), 4, pp 473-497.

Souto-Manning, M. (2016). Honoring and building on the rich literacy practices of young bilingual and multilingual learners. The Reading Teacher, 70(3), 263-271.

Souto-Manning, M. (2017). Is play a privilege or a right? And what’s our responsibility? On the role of play for equity in early childhood education. Early Child Development and Care, 187(5-6), pp. 785-787.

Tazi Morell, Z. and Aponte, A. (2016). Right from the Start: A Protocol for Identifying and Planning Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals in Universal Prekindergarten. Educator’s Voice, 9, pp. 12-25

Tazi, Z., Gunning, A., and Marrero, M. (March 2015). Engaging Parents as Coteachers – Educational Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar15/vol72/num06/Engaging-Parents-as-Coteachers.aspx

Velasco, P., & Fialais, V. (2016). Moments of metalinguistic awareness in a Kindergarten class: translanguaging for simultaneous biliterate development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–15.

Wells Rowe, D. and Miller, M. E. (2015). Designing for diverse classrooms: Using iPads and digital cameras to compose eBooks with emergent bilingual/biliterate four-year-olds. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy (16), 4, 425-472.

Welsch, J. (2008). Playing Within and Beyond the Story: Encouraging Book-Related Pretend Play. Reading Teacher, 62(2), pp. 138-160.

Worthy, J., & Rodríguez-Galindo, A. (2006). “Mi hija vale dos personas”: Latino immigrant families’ perspectives about their children’s bilingualism. Bilingual Research Journal, 30(2), 579–601.

Yoshida, H. (2008). The cognitive consequences of early bilingualism. Zero to Three, 29(2), 26–30.

Acknowledgments

This CUNY-NYSIEB resource was created by Gladys Aponte and Laura Ascenzi Moreno. Ofelia García, Kathryn Fangsrud Carpenter, Cecilia Espinosa, Zoila Morell, Kate Seltzer, Ivana Espinet, and Maite Sánchez, served as advisors to the authors. We would like to give special thanks to the teachers and administrators who provided feedback on this resource.